This Slow Media content is supported by [YOUR ORGANISATION NAME HERE] and is best viewed in a browser.

In This Edition

A single sniff can undo decades, revealing that scent is less about fragrance and more about memory, ego, and the people we once were.

From neon-lit Tokyo bars to late-night train rides, nostalgia drapes itself in cologne, posture, and the ghosts of ambition past.

In these fushigi times, looking back is not mere reflection but an act of survival, a reckoning with the selves we carry and the people close to us now.

Scroll down to read the FULL article

Production Credits

Creator / Writer / Presenter: Angelino Schintu

Produced, Recorded & Engineered at: Fushigi Labs Tokyo

Opening & Closing Voice / Audio Production: Thomas Kinkaid

Theme Music: Original composition Fushigi by Andrew P Partington

PARTNERSHIP OPPORTUNITY

This Slow Media content is supported by [YOUR ORGANISATION NAME HERE]

The Fushigi Times is committed to offering thoughtful, independent, reality-grounded perspectives on global affairs, cultural explorations, and creative thought—made possible with the occasional support from like-minded partners.

...brief Sponsor description...

If there’s a friend, colleague, or fellow traveller you think might enjoy listening to this podcast, consider sending a link their way — subscribing costs nothing, the content is free forever, and it helps keep this Slow Media project alive and growing.

A Scent That Opens the Past

It was a casual, almost affectionate assassination. A line delivered offhandedly, without malice, but a lethal weapon all the same. My bestie, that’s my wife, and I were getting ready to head out for dinner with friends in Tokyo.

I’ve always enjoyed getting dressed. The brand name doesn’t matter much, just as long as it feels and looks good. And that goes for jeans and a T-shirt or a tailored suit. My grooming almost complete, it was time for the final flourish: the shu-shu of a cologne that had been a favourite for decades. Just a small amount. Not enough to announce myself like a teenage boy on the prowl, striding into a nightclub for the first time, shirt gaping to the belly button. Just enough to feel finished, a subconscious flare of a younger me saying, ‘Heads up: style inbound.’

She sniffed the air as I passed by, kind of crinkled her face and said it aloud:

“Ohh. You smell like the Nineties.”

And then, as if nothing had happened, she turned back to applying her lippy, unaware, or maybe very aware, of what she had just triggered. Because that sentence was not merely an observation.

It was a time machine, a trapdoor opening beneath me, releasing the ghosts of a whole decade.

An entire version of myself, crystallised in scent, memory, and perhaps a little touch of ego.

Now, if she had said I looked like the Nineties, I would have fought my corner. I no longer dress like I’m auditioning for a part in Trainspotting. My wardrobe holds no evidence of acid-wash denim, and my hair, removed by choice and replaced by the epic beard, means there’s no contending with the business-in-front, party-in-the-back mullet laws from the start of that decade. Musically, I’ve moved on. Spotify has scrubbed away the evidence of every poor decision made at Shinjuku’s Tower Records. But she was right. I did effuse the aroma of the Nineties.

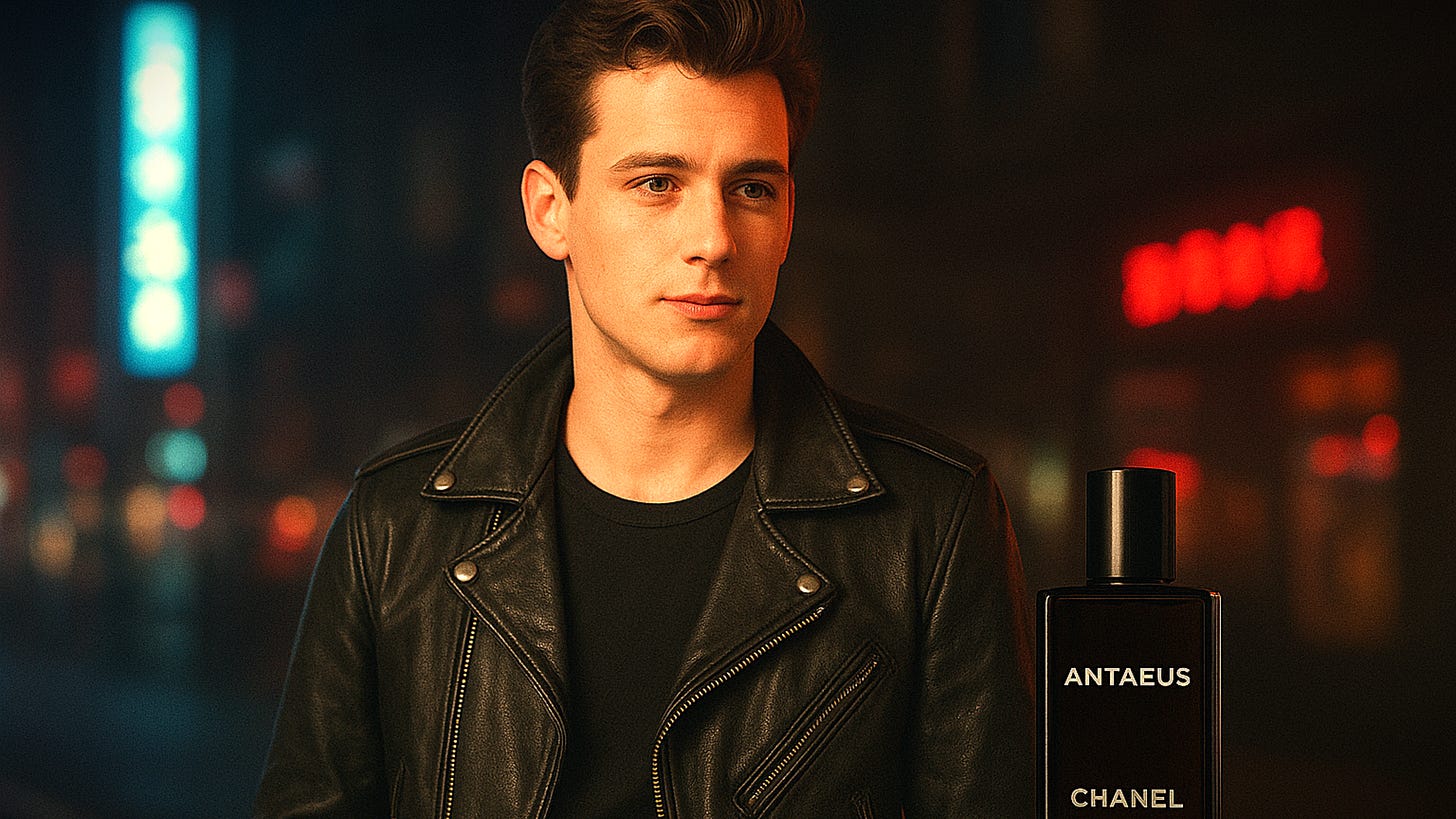

Specifically, it was the smell of Chanel Antaeus, a cologne I once wore with unwavering loyalty throughout my twenties and thirties. In those years, living and working in Japan, Antaeus was one of my few stable companions, another being Michael, my personal manager in those days and still a close mate today. He introduced me to the cologne, which proved reliable, reassuring and a signature as clear as a business card.

To me, it was less a fragrance than a badge of style maturity, proof that I had crossed into the sort of sophistication you might expect from a man of growing sartorial elegance.

The sort of man you could spot in the finer quarters of London, Paris, New York, or Tokyo. After all, nothing says worldliness like dousing yourself in a scent advertised by a man with a jawline sharp enough to slice through glass. Who didn’t want to be that feller?

So to have that era returned to me in a single, unsolicited remark was oddly jarring. Not insulting, not even nostalgic in the sweet sense, but dislocating. As if the past had been bottled, corked, and stored on a shelf, waiting for me to uncork it on a Thursday evening.

I realised, in that moment, that I had not merely kept buying this dark glass bottle for convenience. I had been carrying the past in tangible, nose-bound form, a past that announced itself as clearly as the Nokia ringtone from 2003. One spritz and I was back in that smokey Omote Sando cigar bar, the late-night ramen joint outside the Jingu Stadium where all the taxi drivers congregated around midnight, those long train rides on the Yamanote where, in my head, I created my epic future.

But the problem with secret codes is that sometimes you are the only one left who knows what they mean.

Scent is treacherous like that. You can ignore an old song. You can choose not to watch a film you loved when you were twenty. You can keep your youthful wardrobe buried at the back of a cupboard and pretend you no longer recognise the person who wore it. But you cannot escape smell.

Scent finds you, bypasses reason, crashes through memory, forces you to confront the version of yourself you thought was safely archived.

In that single remark from my wife, I heard more than an aromatic critique. I heard the accusation that perhaps I had not outgrown that decade as fully as I had believed. That some part of me still wanted to be tethered to the young man who wore Antaeus with the smug certainty of immortality. Why else would I have kept buying that same little bottle for so many years? Why else would I, in a fit of misplaced loyalty, apply it before dinner, as though the Nineties could be decanted in liquid form and worn like a fitted Emporio Armani T-shirt?

It made me wonder how many of us are still scented with our own private pasts. Maybe not with cologne, but with traces of old selves that cling despite our best efforts. A watch from a defunct brand. Shoes that no longer fit the decade. Even a ringtone, embarrassingly out of place, lurking on a phone. We preserve these things because they remind us of who we were, and admitting they no longer belong feels a bit like betrayal.

Yes, she was right. I did smell like the Nineties. And once she said it out loud, I could no longer pretend it was just cologne. It was a signal, a confession, a reminiscent form of time travel.

Antaeus: A Baritone in a Choir of Tenors

Antaeus is not subtle. It never was. Launched in 1981, named after the minor Greek demigod son of Poseidon, it belongs firmly to the era before fragrances hid behind euphemisms like “aqua,” “sport,” or “fresh.” Antaeus was thick with leather, oakmoss, labdanum, and something that smelled suspiciously as though it had spent three decades locked inside a mahogany filing cabinet in a law firm that never updated its furniture.

If the modern male fragrance world is a polite chorus of citrusy tenors mumbling about cleanliness, Antaeus is a baritone clearing his throat at the back of the room. This was a scent designed for arrival, not for background ambience. It announced. It projected. It lingered like an unwanted guest at the end of a dinner party. Jacques Polge, who created Antaeus, once described it as “a perfume of power and seduction.” Translation: wear this and people will either move closer or move to another room, but they will not ignore you.

I wore it religiously through the 1990s. For me, it wasn’t just a fragrance. It was costume, posture, energy. Doors seemed to open half a beat earlier. Strangers glanced up with a flicker of curiosity. Even ordering a beer felt upgraded, as though the scent tipped the bartender that I was not there to drink quietly.

If you were in your twenties in Tokyo, trying to signal seriousness, adulthood, danger, and possibly European flair—even if you were none of those things—Antaeus did the trick. I didn’t understand its composition, but I understood its effect. And it wasn’t just internal.

Women noticed. Sometimes directly: “What are you wearing?” Other times, more elliptically: a pause, a lean closer, or a cheeky note slipped into my hand on that same Yamanote Line train, reading simply, “Wow, that cologne,” accompanied by a telephone number and a smile. By decade’s end, I associated Antaeus with magnetism. Not that it made me different, but it suggested I might be. The scent told a story, even if that story wasn’t entirely true yet.

Science corroborates it. A 2009 study published in Physiology & Behavior found that scents like musk, amber, and oakmoss trigger subconscious perceptions of strength and virility. My perceived charm was, at least in part, chemistry masquerading as charisma.

Yet, for all the science, for all the performance, Antaeus was also a costume. Spray enough and you could walk into a room as an international man of mystery, not a journalist scraping deadlines. Perfume companies understand this: in the 80s and 90s, ads didn’t sell fragrance. They sold permission slips to inhabit an identity. Antaeus, with its leather-and-moss presence, sold the role of “the serious man.” A baritone in a choir of tenors.

Tokyo, Celebrity, and Myth-Making in the Nineties

The 1990s were strange in Tokyo. The city metabolised the bubble economy’s excess. Buildings glittered with glass and neon, yet the mood was quieter than the frenetic 1980s. Precision, rhythm, and subtle gestures defined daily life.

In media, it felt like being in the eye of a storm. It was not chaos, but controlled, high-energy cultural and technological transformation. I moved across TV, radio, and glossy print, sometimes unsure how I had earned a press pass or a seat at the right table. Urgency was measured and deliberate, with pauses to consider nuance. Stories were filed with care. Meetings were held over real paper and real whisky. Interviews unfolded in hotel lobbies with lacquered furniture and carefully considered silences. Nothing was flattened by email, algorithms, or Zoom fatigue.

Being young, foreign, and ambitious added a kind of mystique. Before expats became content creators or social-media fixtures, you could move quietly, live fully, and feel part of a larger, almost mythic narrative. The Japanese language, with its coded nuance, trained you to observe more than you declared, a useful inversion of instinct for someone in media and entertainment.

I was part of a small minority of foreigners in the 1990s and 2000s. Every public appearance carried weight. People noticed, everywhere, all the time. Not casually, but in a way that implied a live audience, even if composed of strangers. Women were attuned to subtle cues: presence, posture, scent. A casual walk over Shibuya crossing or through Roppongi to Azabu became a public appraisal. Exhilarating, unnerving, a blend of opportunity and exposure.

I was a DJ on Tokyo’s top-rating morning radio show for six and a half years. Small team, enormous impact, and we changed the trajectory of Japanese broadcasting history forever. Television, modelling, narration: I navigated it all, constantly observed, learning the choreography of attention.

Antaeus was part of that script, not just a fragrance but a tool in self-performance. Scent carried confidence, desire, the aura of being noticed.

It became shorthand for aspiration, a chemical punctuation mark on the sentences of identity I was writing as I reinvented myself again and again.

By the end of that decade, Tokyo rewarded preparation, attention, and audacity. And Antaeus found its moment, scenting ambition in equal measure.

Memory and Nostalgia: Down the Rabbit-hole We Go

After I left Tokyo, I evolved. I stopped being that version of myself, the one who believed a spritz of Antaeus could rearrange the universe.

Scent memory is hardwired. Unlike visual or auditory memory, it bypasses the thalamus—headlong to the limbic system. An edition of Frontiers in Psychology, from 2014, notes olfactory-triggered memories are emotionally potent, persistent. The nose remembers before the mind does.

Scent does more than recall, it romanticises. A faint whiff today distils highlights: recognition in cafés, photo opportunities with fans, autograph requests, nights electric with possibility, attention as currency. It does not recall missed trains, awkward silences, taxi rides steeped in neon-lit regret, even stalkers at the apartment door late at night. Time filters the rough edges, leaving only gold-plated memories.

Male nostalgia is aspirational. We do not merely remember youth; we mourn it, envy it, mythologise it in exile. Rituals that once defined our youth, like clothing, scent, gestures, quietly repeat, echoing former life. Cologne spritzed on a Tuesday evening in 2025 is invocation. Reconnection. A reminder of who I was and how the world responded.

This raises a subtle, uncomfortable question: is it fair to my bestie, my partner, that I occasionally reach backward into a past that predates her? Perhaps it is harmless homage. Perhaps it is unconscious prioritisation of memory over presence. Awareness is unavoidable once scent enters the room.

Memory, nostalgia, and scent form alchemy. They allow a man to revisit his mythological self, play the same scenes, wear the same costume, even if the stage has changed. Seductive, comforting, disruptive.

The trap: mistaking the echo for today’s reality.

Memory in the Age of the Algorithm

Fast forward to the end of 2025. Memory no longer lives in boxes, diaries, or coat pockets. It lives in phones. “On This Day” reminders arrive uninvited, merciless. Digital memory flattens experience into content. Context, nuance, significance all seem secondary. Likes, shares, comments replace quiet reflection.

Holding onto a cologne becomes deliberate. Tangible. Immune to algorithms. Antaeus is a vessel of memory, pulling you bodily, emotionally, unpredictably. One whiff and you’re back in Roppongi’s Motown Bar, or on a late-night train, catching fleeting attention. Unlike Instagram, scent immerses you fully. A small, aromatic time machine.

In a world of algorithmic recollection, unsullied scent becomes radical. It cannot be cropped, filtered, or deleted. That is why, decades later, I occasionally reached for it: not to relive, but to feel, to measure, to remind myself what memory is outside of a smartphone screen.

Memory is fine. Revisiting the past, briefly, is fine. Living there isn’t.

The version of me who wore Antaeus daily was real. He worked hard, navigated a foreign country, learned rules, bent a few, got lucky. Sometimes lonely, always hungry for more. That version belongs exactly where it is—in the past.

The danger lies in needing to be him again. That cologne, James Dean hair, rider’s jacket, Alpha posture. They’re seductive because they carry memory.

The moment usually arrives with quiet reflection, when you realise your sense of self no longer hinges on fleeting approval. Glances and compliments are enjoyable, and there are plenty of them still, thanks to the epic beard. But out here in country-sea Japan, the young bodycon dancers at Julianna’s Tokyo have been replaced by the character-lined faces of women pushing ninety at the local fruit and veg market.

The former is no longer essential. The tools once necessary have done their job. Continuing to use them when they are no longer fit for purpose preserves a shadow self, refusing evolution.

Nostalgia teaches, delights, and reminds, but it can also trap. Memory is a resource, not a residence.

Antaeus serves as a bookmark. It allows me to revisit, to savour, to laugh, to feel just a little longing, but it is not an invitation to reinhabit the past.

Here in Chiba, on Japan’s Pacific Coast near Onjuku Beach, mornings are slow. Coffee, waves, horizon. Blue-zone living. The present is grounded, and there is no need for scented stagecraft. Antaeus is now shelf décor, a memory artefact. The aroma drifts, a smile rises. I honour the past, but live in the present.

Letting Go Without Losing It

I know who I am now. I know how I walk into a room and why I’m there. I’m not hunting, not performing. And I like that man. I trust him. He’s present in 2025, coffee in hand, Google Maps open, searching for a local Izakaya yet untasted.

The scent I wear now is different. Still stylish, but subtle, clean, ordinary. It carries honesty, presence, reality. The past is treasure, an artefact. It reminds me who I was, what I accomplished, what I believed possible. It is no longer a guide, no longer a tool. It is evidence, not instruction.

The grounded man I am now is enough. Lessons, laughter, experience, without the weight of performance. The past was necessary, the rituals were necessary, the attention turned out to be a teacher, not a trophy.

My past was glorious, absurd, thrilling. Worth remembering. But it is not the stage on which today unfolds.

The ordinary, unpretentious, fully present version of myself is the one that really matters.

This is the room I walk into now. And it is more than enough.

📢Want to rebroadcast this?

This original content is part of our Slow Media canon — carefully crafted, independently produced. If you’d like to license, rebroadcast, or syndicate this podcast, let’s talk. We’re open to collaboration — as long as it stays thoughtful, grounded, properly credited… and paid for.

Slow Media Needs Slow Money…